Public Works Oversight: Transparency and Architecture in Service of Democracy

Public works oversight goes beyond construction, it ensures transparency, efficiency, and trust between governments and citizens. Learn how technology, civic participation, and ethics are reshaping the future of hospitals, schools, and infrastructure into more sustainable and corruption free projects.

Public Works Oversight: Transparency as an Architectural Value

Public works oversight is a subject that goes far beyond the technical realm of construction; it enters the field of democracy, ethics, and architecture as a cultural symbol. In every country, roads, hospitals, schools, and government buildings represent much more than physical structures: they are tangible manifestations of trust between the State and its citizens. That is why these types of projects are always under the watchful eye of society.

When we talk about oversight, we refer to the set of control, supervision, and auditing mechanisms that ensure public resources are used correctly, efficiently, transparently, and with integrity. Without it, the risks of corruption, cost overruns, and delays multiply, undermining the legitimacy of governments and the sense of belonging within communities.

Transparency, understood as a guiding principle, is not only related to open data and accountability, but also to an architectural value that permeates public spaces. An open building—created with participatory design and subject to strict oversight during construction—conveys trust and strengthens the social contract.

Historical Context of Public Works Oversight

Traditional Models of Control

Since ancient times, governments have understood the need to control the use of resources allocated to public works. In the Roman Empire, for example, censors were responsible for supervising the construction of aqueducts, roads, and amphitheaters. These officials reviewed contracts, inspected materials, and punished those who failed to comply with the established standards.

During the Middle Ages, the construction of cathedrals and city walls was under the control of guilds, which not only guaranteed quality but also acted as internal oversight bodies. Later, with the consolidation of modern States in Europe, royal treasuries and auditing offices emerged to monitor expenses in fortresses, roads, and ports.

These primitive models, although limited, laid the foundation for today’s control systems. The main difference is that modern oversight no longer relies solely on appointed officials but also on digital tools and citizen participation.

Ironically, some of these ancient practices still seem to persist today often without proper control.

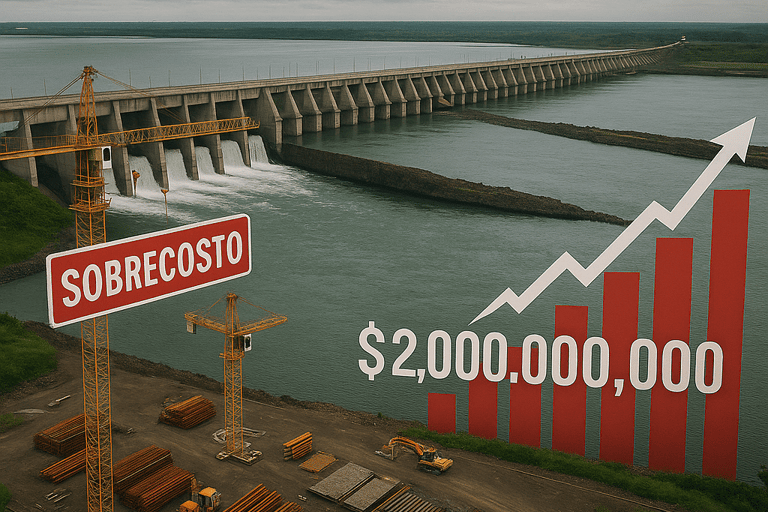

History is also marked by examples of what happens when oversight is weak or nonexistent. In Latin America, the 20th century was plagued with massive infrastructure projects that doubled or tripled their original costs. Scandals such as the Yacyretá Dam in Argentina and Paraguay labeled a “monument to corruption” due to its inflated costs—illustrate how the absence of oversight can destroy the legitimacy of a public work.

In other regions, such as Africa and Asia, international aid destined for infrastructure projects has often been diverted through corruption networks, leaving behind incomplete or poor-quality structures. These cases generate a double loss: economic waste of public resources, and social damage through the erosion of citizens’ trust in governments and institutions.

Transparency as an Architectural Principle

Beyond aesthetics, ethics, and responsibility in the architectural field, transparency has long been associated with modern design: glass facades, open spaces, and structures that embrace visual openness. However, in public works, this concept goes beyond aesthetics it becomes an ethical value and an institutional responsibility.

When a government building is designed and constructed under principles of transparency, it not only reflects openness in its form but also in its management processes. The way contracts are awarded, materials are selected, and budgets are managed is an essential part of this ethical architecture.

In other words, oversight and transparency should be as visible as the columns and beams of a building. If architectural design communicates openness and accessibility, then project management must align with the same philosophy, creating functional, comfortable spaces where citizens feel at ease.

Public Buildings as Symbols of Trust

The architecture of public buildings carries tremendous symbolic weight. They are not merely offices where documents are processed or policies are managed; they are spaces that represent the State itself, spaces that show how both the environment and services improve to ensure proper care and functionality.

Examples such as the Berlin Parliament (Reichstag), renovated with a glass dome symbolizing democratic openness, demonstrate how architecture can become a powerful metaphor for institutional transparency. Similarly, in Scandinavian countries, community centers are designed with glass walls that aim to transmit proximity, transparency, and trust to citizens.

In Latin America, some recent projects such as the open justice centers in Mexico have embraced this philosophy, promoting accessible spaces designed to strengthen the relationship between citizens and institutions.

Modern Oversight Tools

Digital Technology and BIM (Building Information Modeling)

Contemporary public works oversight has taken a qualitative leap forward thanks to technological innovation. The use of BIM (Building Information Modeling) makes it possible to create three-dimensional digital models containing detailed information about every aspect of a project: materials, costs, execution timelines, and future maintenance.

While these technological tools enhance control, they do not diminish the value of professionals who, for years, have carried out these tasks through traditional methods with quality results. However, it is also true that in some cases this type of oversight remains weak, absent, or even manipulated for the benefit of contractors and officials.

With BIM, supervisors can detect budget inconsistencies, anticipate delays, and evaluate the quality of materials even before construction begins. This level of precision makes it harder to manipulate figures and contributes to more transparent processes.

Real-Time Audits and Citizen Participation

Another key innovation is the implementation of open government platforms. These digital tools allow both authorities and citizens to access real-time information about the status of public works: physical progress, budget execution, bidding processes, and contracted suppliers.

In countries such as Chile, online portals display the progress of projects funded with public resources, enabling citizens to participate in oversight. This model of “social oversight” has become a powerful mechanism against corruption.

Current Challenges in Public Works Oversight

Hidden Costs and Cost Overruns

One of the most recurring problems in public works is the emergence of hidden costs. These appear as additional expenses that were not included in the original budget and, in many cases, result from non-transparent practices. It is reasonable to consider contingency funds in certain budgets since every project is different. However, in Latin America, it is common for the total cost of a project to be inflated in order to generate higher profits, cover kickbacks to contracting officials, or obtain other private benefits.

Cost overruns are often justified with technical arguments, such as design changes, unforeseen geological difficulties, or rising material prices. However, international studies have shown that in a high percentage of cases, these increases are due to poor planning or deliberate manipulation of figures to favor certain contractors.

In Latin America, for example, reports from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) have indicated that up to 30% of the final budget for some projects can be attributed to unjustified cost overruns. This reality reinforces the need for stricter oversight mechanisms and exemplary sanctions against those who manipulate public funds.

Technical Complexity and Bureaucracy

Large infrastructure projects require the participation of multiple stakeholders: architects, engineers, contractors, subcontractors, suppliers, and public officials. This long chain of responsibilities often turns into a complex bureaucratic network that makes tracking expenses difficult. For this reason, it is essential to rely on qualified, experienced, and incorruptible personnel.

Each additional layer of contracting increases the chances of discretion and corruption. Moreover, excessive bureaucracy often slows down oversight processes, allowing irregularities to go unnoticed until it is too late.

In this sense, one of the greatest challenges is to harmonize internal control systems with external oversight, ensuring that the process is agile and effective without becoming an obstacle to project development.

International Success Stories

Europe: Transparent and Sustainable Projects

Europe has been a pioneer in implementing transparent and participatory oversight systems. In Norway and Denmark, for example, all public works contracts must be published on digital platforms accessible to any citizen. In addition, audit reports are public, allowing journalists, academics, and civil society organizations to exercise indirect yet effective control.

In Germany, the use of the BIM model (Building Information Modeling) has been integrated into large-scale infrastructure projects, making it possible to detect irregularities in the early stages and avoid multimillion-dollar cost overruns.

Most importantly, in many of these countries oversight is not only focused on financial aspects but also on environmental sustainability and energy efficiency, ensuring that projects are transparent while also respecting the environment.

Latin America: Progress and Obstacles

The Latin American region presents a mixed picture. On one hand, countries such as Chile and Uruguay have made notable progress in transparency, with open public procurement systems recognized by international organizations. In these nations, any citizen can verify online the contracts, amounts, and awardees of state-funded projects.

However, in other countries, serious structural corruption problems persist. The Odebrecht scandal, which involved multiple nations in the region, revealed how gaps in oversight systems enabled the payment of multimillion-dollar bribes in exchange for project awards. This case made it clear that beyond digital tools, political will and institutional independence are decisive factors for effective oversight.

In Ecuador, for example, several public works have been plagued with inflated costs, including hydroelectric plants, Millennium Schools, and the Government Financial Management Platform in northern Quito. This building not only suffered from a poor design (leaving aside the well-known aesthetic deficiencies) but also from a dysfunctional layout: underutilized spaces, insufficient sanitary facilities for the number of users, a deficient evacuation system, facades that are difficult to maintain, and outdated technological systems despite having been inaugurated with great fanfare as one of the country’s most advanced projects.

After more than eight years of occupancy, it still lacks habitability permits and sufficient services such as security and cleaning. Moreover, public institutions occupying the building pay exorbitant “maintenance fees” essentially disguised rent that in some cases amount to nearly one million dollars annually. This situation clearly illustrates how a project with cost overruns lacked proper oversight, undermining its legitimacy and efficiency.

Benefits of Effective Oversight

Citizen Trust and State Legitimacy

Oversight of public works is not merely an accounting exercise—it is a pillar of political legitimacy. When citizens perceive that projects are executed transparently, their trust in institutions grows, which in turn strengthens democratic stability.

A concrete example is Finland, where transparency in public management has contributed to one of the highest levels of institutional trust in the world.

Reducing Corruption and Improving Efficiency

Effective oversight reduces opportunities for corrupt practices and ensures that projects are executed within budget and on schedule. This not only benefits citizens with high-quality infrastructure, but also prevents the loss of millions that could otherwise be allocated to social areas such as health and education.

In fact, according to OECD data, countries with robust oversight systems save between 10% and 20% of their public works budgets, representing a direct positive impact on the national economy.

Strategies for the Future

Artificial Intelligence and Big Data

The implementation of emerging technologies promises to transform public works oversight in the coming decades. The use of artificial intelligence and big data analysis will make it possible to identify anomalous spending patterns, anticipate financial risks, and detect potential cases of corruption even before they occur.

These tools, combined with blockchain-based smart contracts, will ensure safer, more transparent, and tamper-resistant processes.

Participatory Architecture and Open Design

The oversight of the future must also integrate citizens not only in supervision but in the design of public works themselves. Models of participatory budgeting and open urban planning processes allow communities to become active stakeholders in development, reinforcing the bond between architecture, transparency, and democracy.

Examples of this approach can be found in cities such as Porto Alegre, Brazil, where participatory budgeting has enabled citizens to directly decide which projects to fund, thereby strengthening social oversight.

Public Works Oversight in the Current Context: Global Challenges

Public works oversight cannot be understood solely within a local or regional framework. In a globalized world where foreign investment, international loans, and multinational partnerships shape the direction of many projects, oversight mechanisms must adapt to a global scale.

Institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) have, over the past decades, required beneficiary countries of public works financing to implement strict and transparent control systems. However, in practice, these requirements are often fulfilled only formally, without translating into real change in project management.

The lack of transparency in large-scale projects not only affects the countries where they are executed, but also international investors, who see the profitability of their projects decrease when cost overruns, delays, or corruption scandals arise.

The Role of Citizens in Contemporary Oversight

While state authorities are obliged to supervise the use of public resources, international experience shows that oversight is far more effective when it becomes a collective exercise.

In countries like Colombia, “citizen watchdogs” (veedurías ciudadanas) have been implemented mechanisms in which community groups monitor the progress of local works, report irregularities, and demand explanations from the relevant authorities.

Citizen participation not only strengthens transparency but also increases the sense of ownership and belonging to the project. When the community is involved from design to supervision, it is more likely that projects will respond to real needs rather than to political or economic interests.

The Ethical Dimension of Oversight

Beyond technical tools, public works oversight has a deep ethical dimension. Every dollar wasted on corruption or inefficiency is not only an economic loss, but also a denied opportunity for those who need it most.

An unfinished hospital due to lack of oversight means lives at risk. A poorly built road resulting from bribery represents accidents, delays, and higher transportation costs. The ethics of transparency, therefore, is not an abstract value, it is a moral imperative tied to collective well-being.

In this sense, oversight should be understood as an act of social justice, ensuring that public resources truly benefit citizens.

Architecture and Oversight: The Symbolism of Transparency

Architecture is not neutral: it transmits messages, reflects values, and shapes citizens’ perception of institutions. That is why, when we speak of transparency as an architectural value, we refer to a practice that must be evident both in the physical design of buildings and in the management processes that sustain them.

Examples such as the London City Hall, designed by Norman Foster with a curved glass façade, demonstrate how architecture can symbolize openness and accessibility. Similarly, Scandinavian parliament with open public spaces and visible debate halls incorporate transparency as a central element of their architectural design.

In Latin America, some local governments have begun to adopt this symbolism in public works, building open justice centers, public universities with accessible auditoriums, and libraries with glass walls. These structures send a clear message: knowledge, justice, and public services must be open to everyone.

Oversight, Sustainability, and the Future of Public Works

Transparency in public works cannot be separated from another central value of our time: sustainability. A project executed opaquely is not only at risk of corruption, but also of causing severe environmental impacts.

Today, many oversight systems integrate sustainability indicators, evaluating whether materials are environmentally friendly, whether construction respects local biodiversity, and whether energy efficiency standards are met.

Transparency, in this sense, also means openly showing the environmental and social impacts of projects, so that citizens can decide whether the benefits truly outweigh the costs.

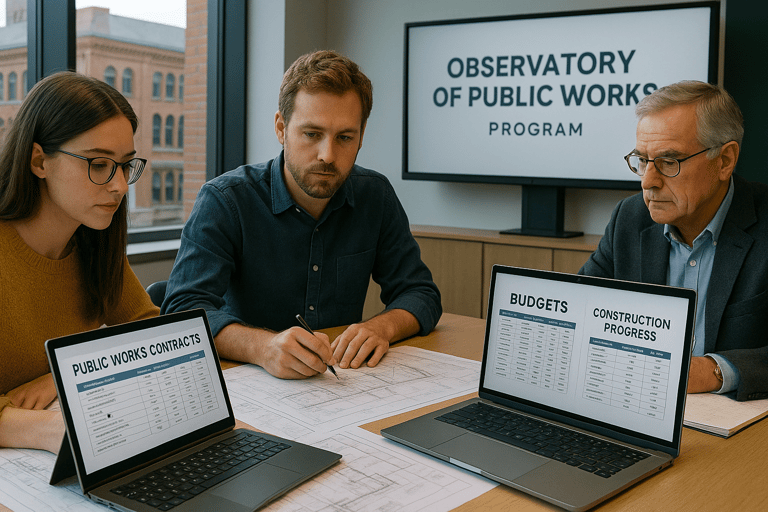

The Role of Universities and Professionals in Oversight

Another key player in this transparency ecosystem is universities, professional associations, and guilds of architects and engineers. These institutions not only train future professionals in ethics and responsibility but can also play an active role in supervision.

Some schools of architecture and engineering in European and Latin American countries have developed public works observatory programs, where students and faculty participate in reviewing contracts, budgets, and construction progress. This not only provides additional oversight but also educates new generations in the practice of transparency.

FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

1. Why is oversight crucial in public works?

Because it prevents corruption, ensures efficient use of resources, and strengthens citizens’ trust in institutions.

2. What role does transparency play in public architecture?

Beyond aesthetics, architectural transparency communicates openness, trust, and democratic commitment.

3. What are the main modern oversight tools?

BIM (Building Information Modeling), open government platforms, artificial intelligence, and blockchain.

4. What challenges does Latin America face in terms of oversight?

Structural corruption, lack of institutional independence, and excessive bureaucracy.

5. What benefits does effective oversight generate?

Reduced cost overruns, economic efficiency, higher-quality projects, and political legitimacy.

6. How can citizens participate in oversight?

Through social audits, digital transparency platforms, and participatory budgeting processes.

Conclusion: Transparency as the Foundation of the Architectural Future

Public works oversight should not be seen as a bureaucratic obstacle or an additional administrative requirement, but as a fundamental pillar of democracy and sustainable development.

Transparency, understood as both an architectural and ethical value, guarantees that every dollar invested in infrastructure translates into real benefits for citizens. A bridge is not just a concrete structure, it is a symbol of connection between communities. A hospital is not just a white-walled building, it is a symbol of care and dignity. And a parliament is not just a legislative chamber, it is a symbol of trust in democracy.

The future of public architecture and government management depends on our ability to integrate oversight, technology, citizen participation, and ethics at every stage of projects. Only then will public works become truly open, transparent, and representative of the values a society seeks to embody.

Ultimately, transparency is not merely a control mechanism, it is the foundation upon which democratic, inclusive, and sustainable architecture is built.